An “Agile Burn-Down” Can Be a Misleading and Terrible Tool…

…Unless you consider getting to the edge of a cliff on time a success.

The “burn-down chart” is a favorite among managers whose teams use purported “Agile” methods such as SAFe and Scrum.

The reason given is that it helps them to see if they are on track to meet their product timeline.

It’s BS. Here’s why:

You don’t really know what stories you should have until you are deep into the work.

A product is NOT the roll up of its many features.

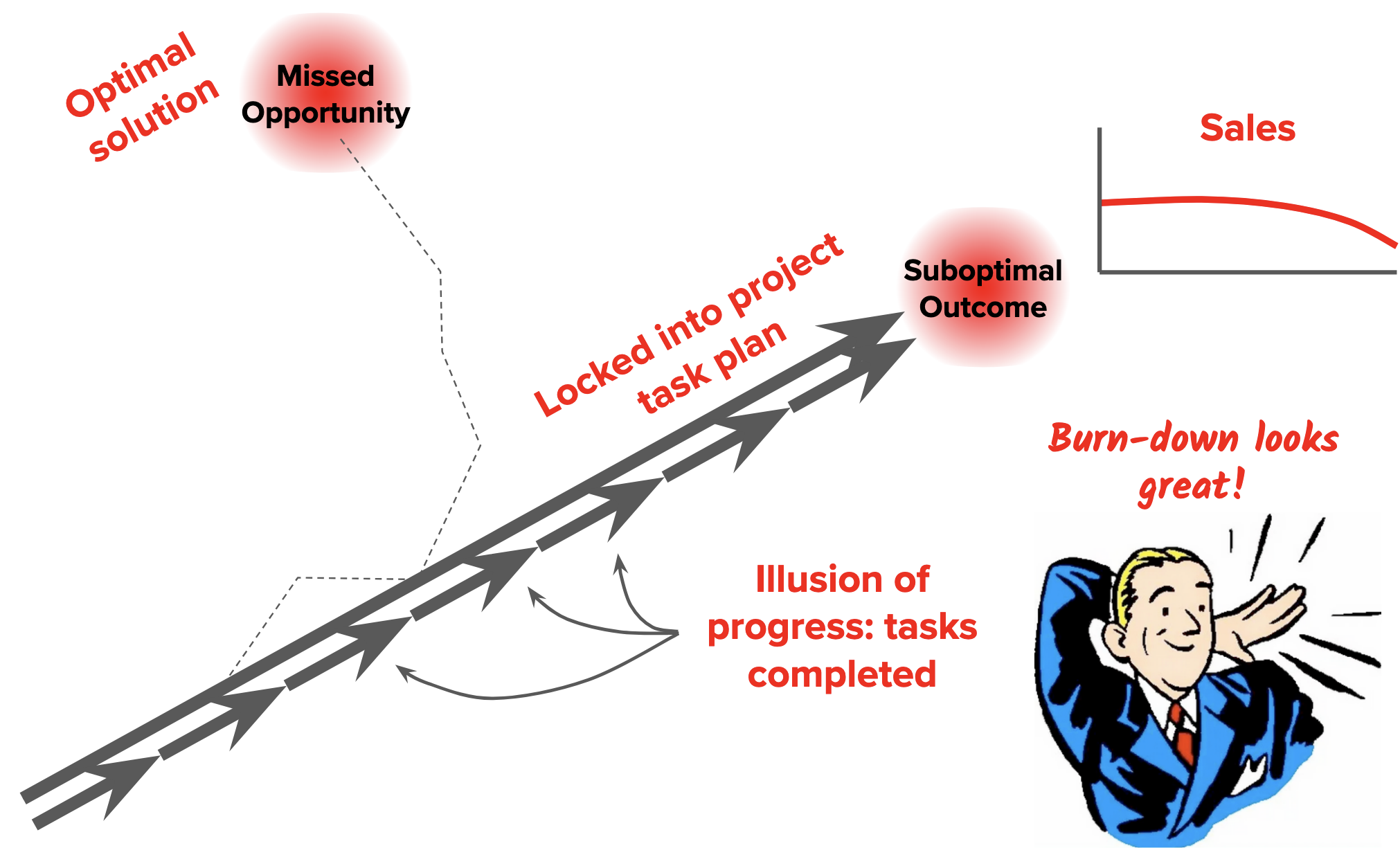

The ramification of number 1 is that if you execute to plan, you will build a lot of the wrong things – and the product will do poorly in the market. The ramification of number 2 is that a lot of loose ends will be left hanging when your burn-down reaches zero: the product will be brittle, hard to operate, clunky to use, and have a half-done feel. Your MVP will not actually be viable – not in a market success sense.

Let’s examine these situations up close.

Why Your Initial List of Features is Usually Wrong

It is extremely common to realize that features that you envisioned early on are not the best.

Designing and developing a product is highly creative. It is not repeatable work: you never design the same product twice.

As you get deep into the work, your understanding of the evolving product improves. Thinking through how pieces will work and fit together forces you to think through how people will use it. It is extremely common to realize that features that you envisioned early on are not the best – that there is a better way: a different feature set might actually be better for the users.

If you build your plan around tasks, your plan will be extremely inflexible, and will lead you to develop the wrong things.

This ever-evolving understanding is also true for the technical design. As a programmer, I usually write down a task list when I start to program something. What then happens is that when I get half-way through the list, I change my approach, redo some things, and then the entire second half of the task list is irrelevant, because I have changed my approach in significant ways.

Note that I have 40 years of development experience, have built compilers and other very advanced things, and was CTO and co-founder of a successful company that built mission-critical things for FedEx, McKesson Pharma, and many others: in other words, if I change my mind half-way through my programming tasks, then you can bet others do too, and it is not from incompetence – it is just the way that this works.

The reality is that you cannot fully task out a software or engineering development effort: half of your tasks will be wrong. That means that if you build your plan around tasks, your plan will be extremely inflexible, and will lead you to develop the wrong things.

Why Features Do Not Roll Up to a Complete System

The creative nature of product development means that you cannot know what tasks are required to complete it. Let’s consider software: software is an algorithm. Once you have fully defined the algorithm, you are done. But the only way to know how many branches there are in the algorithm is to design it. Yet the number of branches are, in essence, the number of “pieces” to build. Thus, you cannot know how many pieces must be built until you are done.

I think you see the dilemma: you cannot sum up the pieces until you know all the pieces; but you cannot know all the pieces until you are done.

You cannot sum up the pieces until you know all the pieces; but you cannot know all the pieces until you are done.

Also, what happens when people (managers) take a purely feature list or task list approach to developing a product, developers will think of all kinds of small things that are important for the product’s health, usability, and reliability, but since those things are not in the feature list, they will get skipped. The resulting product will be brittle and feel incomplete.

Here’s the bottom line: no matter how much effort you put into creating a complete list of features or tasks, it will leave out important things that you cannot think of until you are deep into the work.

What to Do Instead

There is no “process” for this; but here is a kind of meta process. It’s a meta process because it is behavioral – it is not something that you can mindlessly execute. You have to think, and use judgment about when to do each thing, and what form that should take in each situation.

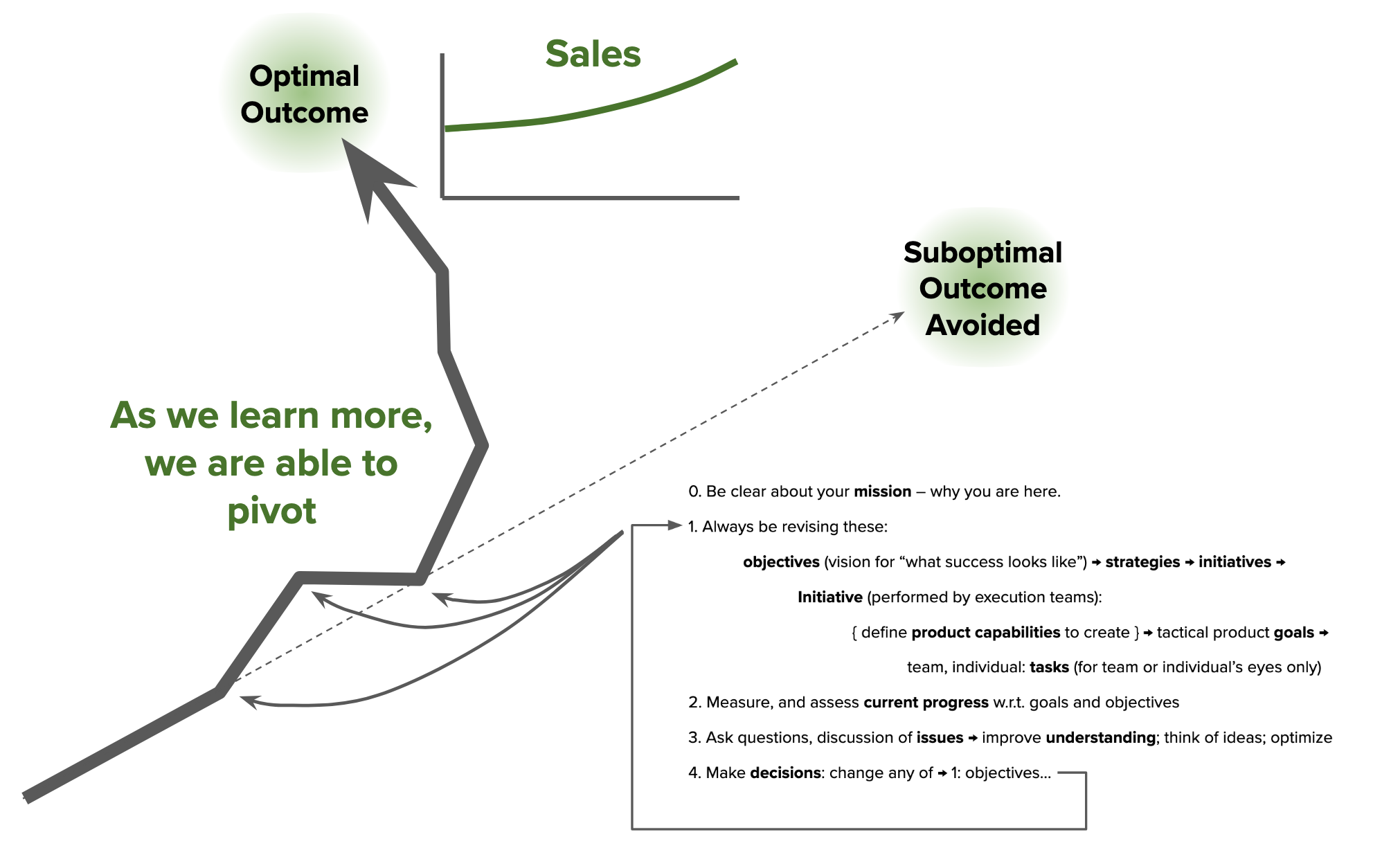

Instead of obsessing over task completion, this approach is focused on issues, improving understanding of what is needed and what can be done, and how to optimize from where we are at each point in time. Teams and individuals are left to worry about what tasks will help them to achieve the goals that they set – goals that are always being adjusted to meet evolving objectives.

We are also laser focused on the objectives – not the tasks. We should always be asking ourselves, Will this really succeed? Or now that we know more, should we adjust it somewhat? Does success actually look different from what we thought at the outset?

We should always be asking ourselves, Will this really succeed? Or now that we know more, should we adjust it somewhat?

What makes this work is not a process flow. Process flows don’t make anything creative work well: they are like painting by numbers – you won’t get something that anyone would want to hang on a wall (unless it is your mother’s wall).

A process flow is not what generates success for creative work like product development. What generates success is good leadership in the flow of activities above. That flow is not cadence-based or scripted in any way: it is entirely driven by discussions, realizations, and subsequent decisions. And if we have “pace-setting” leadership, to use a term from Daniel Goleman, it occurs at the fastest rate at which those things can occur – it is not constrained by a calendar.

This is how SpaceX works.

Why This is the Lowest-Risk Approach – Even Though It Feels Scary

This approach feels scary if you are accustomed to the comfort of a cadence-based pro forma process. A pro forma process makes you feel like you are getting things done: simply perform the steps. But are you actually building a product that will be successful? Leaders who rely on pro forma processes are not pace-setting leaders: they are administrators.

The burn-down feels comfortable: it is like a bed-time story telling you that everything is alright. But it is not reality: it does not tell you the true state of the product you are developing. Instead, it tells you a comforting story – that the things that you thought you needed to do, back when you had a very limited understanding of what was involved or needed, are almost done; but it doesn’t tell you if what you actually need is done or even understood.

Completing tasks that were based on a poor understanding is the wrong approach.

Tracking tasks completed is a very poor measure of progress: it ignores the learning that can occur in the course of work, which would inform a change of direction.

The right approach is to continuously adjust your goals, to track your evolving understanding, always optimizing what can be completed or created in the time you have left, and always adjusting the target features based on that optimization.

Focusing on issues, and always questioning one’s direction and goals, encourages continuous optimization of one’s path as one learns in the course of work.

Instead of a “fire-and-forget” approach, you are like a heat-seeking missile, always changing course to track the target.

By the way, we built a tool that works this way: instead of tracking tasks, it is entirely based on supporting the planning-and-execution cycle described above. It is called Streamline, just so you know. It’s not something to add to your current suite: it replaces tools like Jira, so you save on the cost of those, which has been rising.

What About Scrum?

I mentioned SAFe and Scrum, but how does this apply to Scrum, which is based on two-week increments?

Scrum puts undeserved focus on a process, when most of the focus should be on behavior – on the inclination to ask questions and to drive discussion on issues. Tools and methods that are built around task tracking encourage task-oriented behavior and discourage outcome-focused behavior.

A true Agile tool would be about goals and objectives – not about tasks or “tickets”.

Also, Scrum is a one-size-fits-all for product development. That doesn’t make sense: the way that a team of experienced people work best is very different from the way that a team of junior people work best. We all know this intuitively, but people have been so deeply indoctrinated by Scrum, that they don’t question the idea that everyone should follow that identical process.

Imagine telling a group of highly experienced developers that they have to split their work into tiny stories. Not only is that insulting, but it prevents them from taking ownership of problems to be solved, replacing that sense of ownership with tasks. Scrum creates a task focus. Agile wasn’t meant to be like that. And by the way, SpaceX – perhaps the most truly agile company in the world – doesn’t force its people to split work into tiny tasks.

Jira, the most widely used project tool for Scrum teams, is fundamentally a task-based system, with views layered on top to suit Scrum. But a true Agile tool would be about goals and objectives – not about tasks or “tickets”: that’s why one of the four “Agile” values is “Responding to change over following a plan”. A true Agile system would support change first and foremost. Instead of tracking tiny tasks, it would encourage leaders to “trust the team to get the job done” – to solve problems and create capabilities – at least for the experienced workers, not in a stand back and hope for the best way, but in an inquisitive and pace-setting way.

The Truth

Product development is high risk. There is no by-the-numbers approach that removes the risk of the product not succeeding. If someone tells you that there is, they are lying to you.

The reality is that the approach to work in an initiative should be designed, just as one would plan a long road trip before getting in a car.

Think about that – that’s important: smart leaders don’t just stand up cookie-cutter teams and stand back. They collaborate with the team leads to design how things will work.

The Scrum community often cites the IBM PC project as an example of a project that inspired Scrum. Yet that project was so successful because at its outset a group of hand-picked experienced managers locked themselves in a room for a week and planned out how the project would be done – not the tasks, but what would need to happen – the problems to be solved and the milestones – and who would make each happen and key strategies.

When planning an initiative you should consider things like, Is the team experienced? Is the work complex? What expertise do we need? Which of the team members have done similar things before? Have these people worked together before? What skills does the team lead have? Who else on the team has leadership skill and of what kinds? How many teams are there? How urgent is the work? How mission-critical is it? What kinds of risk are there and how severe are the risks?

These things make a huge difference. Simply defaulting to Scrum is, frankly, an abdication of managerial duty, although I blame the Agile community and Scrum trainers for aggressively promoting the incorrect – indeed nonsensical – idea that Scrum is a universal approach applicable for all development teams.

Any pro forma process can easily cause you to focus too much on the rules of the process and not pay enough attention to issues and the uniqueness of the situation. You will tend to assume that the process takes care of risk, but risk is most effectively handled by asking questions and trying to understand issues, and that doesn’t require a process: it requires proactive attention and a desire to get to the root cause of things.

The only formula for managerial success of product development is to focus on your own behavior and the behaviors of everyone else, especially people in leadership roles. That’s not a process. Some important behaviors include being goal-focused, being issue-focused, being inquisitive, being open-minded, being decisive, being responsible, being an organizer, and being thoughtful. Those are what matter.

Not checking off tasks.